It's An Uphill Battle

According to Greek mythology, Sisyphus was a king who angered the gods by his craftiness and trickery, even having once cheated death. His eternal punishment was to push a boulder up a steep hill, only to watch it roll back down just before he reached the top. Sisyphus would then have to start over, pushing the boulder back up again, in a never-ending cycle of effort without achievement.

Thus, the term "Sisyphean endeavor" refers to a task that is both laborious and futile. It represents the endlessness futility of pursuing worldly success

No matter how many times we push our boulder up the hill of worldly gain and materialism, it always comes right back down. This is the reality we all face until God infuses divine purpose into our otherwise pointless lives.

"Now this I say and testify in the Lord, that you must no longer walk as the Gentiles do, in the futility of their minds" (Ephesians 4:17, ESV).

"Many are the plans in the mind of a man, but it is the purpose of the Lord that will stand" (Proverbs 19:21, ESV).

It All Goes Back In The Box

John Ortberg writes:

My grandmother ... was a lovely woman, but she was the most ruthless Monopoly player I have ever known in my life. Imagine what would have happened if Donald Trump had married Leona Helmsley and they would have had a child. Then, you have some picture of what my grandmother was like when she played Monopoly. She understood that the name of the game is to acquire.

When we would play when I was a little kid and I got my money from the bank, I would always want to save it, hang on to it, because it was just so much fun to have money. She spent on everything she landed on. And then, when she bought it, she would mortgage it as much as she could and buy everything else she landed on. She would accumulate everything she could. And eventually, she became the master of the board.

And every time I landed, I would have to pay her money. And eventually, every time she would take my last dollar, I would quit in utter defeat. And then she would always say the same thing to me. She’d look at me and she’d say, “One day, you’ll learn to play the game.” I hated it when she said that to me. But one summer, I played Monopoly with a neighbor kid–a friend of mine–almost every day, all day long. We’d play Monopoly for hours.

And that summer, I learned to play the game. I came to understand the only way to win is to make a total commitment to acquisition. I came to understand that money and possessions, that’s the way that you keep score. And by the end of that summer, I was more ruthless than my grandmother. I was ready to bend the rules, if I had to, to win that game. And I sat down with her to play that fall.

Slowly, cunningly, I exposed my grandmother’s vulnerability. Relentlessly, inexorably, I drove her off the board. The game does strange things to you ... She was an old lady by now. She was a widow. She had raised my mom. She loved my mom. She loved me. I took everything she had. I destroyed her financially and psychologically. I watched her give her last dollar and quit in utter defeat. It was the greatest moment of my life.

The author continues:

And then she had one more thing to teach me. Then she said, “Now it all goes back in the box–all those houses and hotels, all the railroads and utility companies, all that property and all that wonderful money–now it all goes back in the box.” I didn’t want it to go back in the box. I wanted to leave the board out, bronze it maybe, as a memorial to my ability to play the game.

“No,” she said, “None of it was really yours. You got all heated up about it for a while, but it was around a long time before you sat down at the board, and it will be here after you’re gone. Players come and players go. But it all goes back in the box.”

And the game always ends. For every player, the game ends. Every day you pick up a newspaper, and you can turn to a page that describes people for whom this week the game ended. Skilled businessmen, an aging grandmother who was in a convalescent home with a brain tumor, teenage kids who think they have the whole world in front of them, and somebody drives through a stop sign. It all goes back in the box–houses and cars, titles and clothes, filled barns, bulging portfolios, even your body.

"I have seen all the things that are done under the sun; all of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind" (Ecclesiastes 1:4).

Of Selfies and Sacrifice

Czech gymnast Natalie Stichova is just one of the latest of so many to tragically die while attempting to take a selfie. In August 2024 she travelled to the mountains of Bavaria with friends to capture the perfect selfie moment, posed atop the peak the majestic Tegelberg Mountain with the famous Neuschwanstein Castle (the model for Disney's Cinderella castle) spectacularly centered in the background. But this fairytale moment quickly descended into the stuff of horror films when she lost her balance, falling some 250 feet to a tragic end. Though she survived the initial fall, she died 6 days later having never regained consciousness.

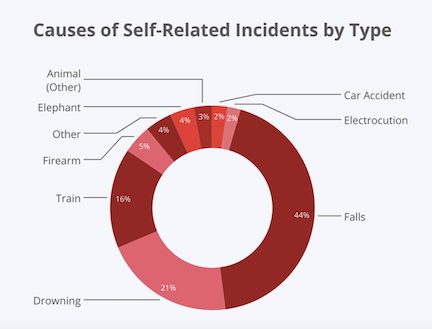

According to a comprehensive global study, at least 425 people have died from selfie-related incidents between March 2014 and May 2025, spanning 49 countries. Falling from heights accounts for nearly half of all deaths and injuries. And these statistics represent just the "obvious" or forensically "verifiable" deaths by selfies.

This does not factor in the countless deaths that were peripherally related to taking a selfie or were selfie-related but that could not be verified as such during the autopsy or at the crime scene. Odds are, the number of selfie-related deaths and injuries is likely much higher.

Spiritual self-centeredness is just as dangerous.

According to one commentary:

Looking out for our own interests is natural. In fact, Jesus uses our innate self-interest as a basis for gauging our love for others: “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31). In other words, in the same way that you (naturally) love yourself, learn to love others. Our universe should be others-centric, not self-centric. As Paul puts it, “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others” (Philippians 2:3–4). This command leaves no room for self-centeredness.

Being focused on oneself usurps the biblical commands to love and care for our neighbors (John 13:34–35), to not pass judgment on others (Romans 14:13), to bear others’ burdens (Galatians 6:2), and to be kind and forgiving (Ephesians 4:32). Being self-centered is directly opposed to the clear command, “No one should seek their own good, but the good of others” (1 Corinthians 10:24). There are many other similar commands calling for selfless sacrifice and service to others (Romans 12:10; Ephesians 5:21; Galatians 5:26).

It concludes:

Every act of self-love is rebellion against the authority of God. Self-centeredness is rooted in one’s fleshly desire to please self more than God. In essence, it is the act of supplanting God’s authority with one’s own ego.

In such conditions, you dangle on the precipice of spiritual demise. Take your eyes off yourself. Step back from the edge. Take off the binders, and turn the lens of your focus to the needs of others!

“No one should seek their own good, but the good of others” (1 Corinthians 10:24, NIV).

"Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves. Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others" (Philippians 2:3-4, ESV).